Performance bonds have migrated from the construction site to the long tail of operations: multi‑year maintenance, facilities management, software support, fleet servicing, even janitorial contracts for large campuses. Owners and asset managers ask for them when service continuity matters and switching costs are painful. Contractors bristle at the perceived friction and carrying cost. Insurers, sitting between them, try to price risk that is part technical, part behavioral. After twenty years negotiating, placing, and enforcing these bonds on both public and private deals, I’ve learned that the instrument works only when everyone understands what it actually guarantees and what it plainly does not.

This piece unpacks performance bonds for maintenance and service agreements, not just their mechanics, but also the messy points where projects fail, invoices pile up, and phones go unanswered at 3 a.m. The goal is practical: give you enough context and examples to specify the right bond, price it realistically, and use it when the service provider falters.

What a performance bond means in a service context

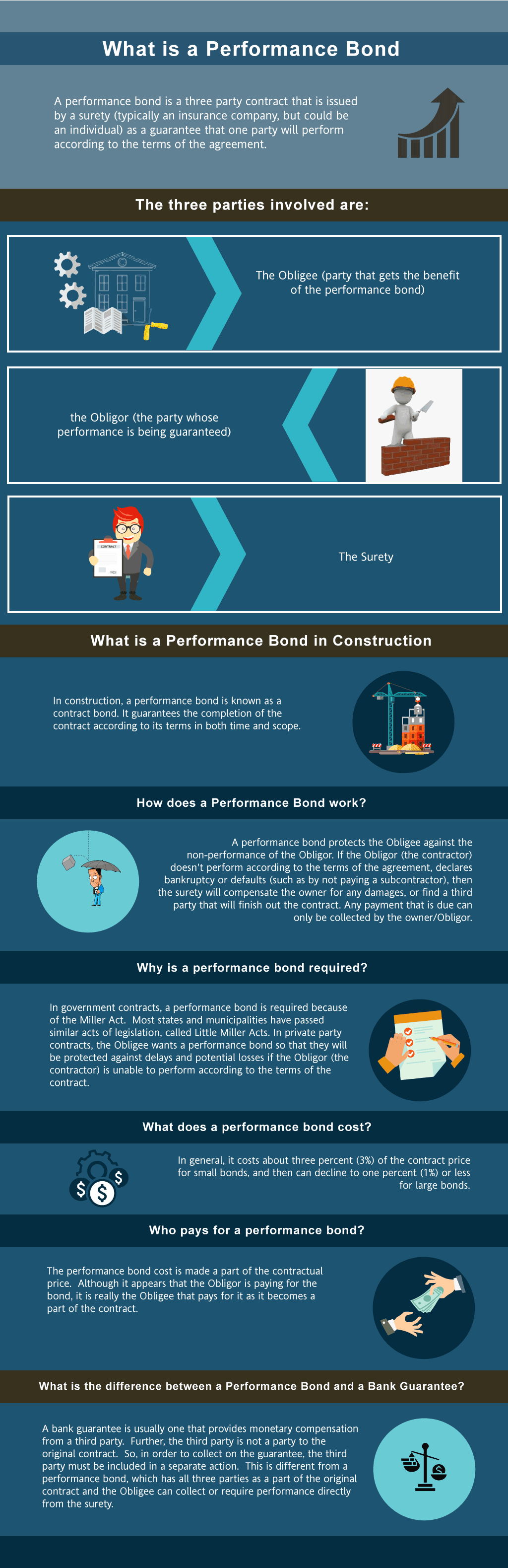

At its core, a performance bond is a three‑party agreement. The principal is the service provider. The obligee is the owner or client. The surety is the company underwriting the obligation. The bond guarantees the principal’s performance of the underlying contract. If the principal defaults, the obligee can call on the surety to step in subject to the bond’s terms.

That sounds straightforward on a build‑and‑deliver contract where completion can be measured against a set of drawings. Service and maintenance work is murkier. Performance is continuous, interruptions may be partial, and “default” often looks like gradually missed SLAs, not a dramatic walk‑off. That ambiguity is where claims stall. The remedy is a contract that converts service quality into measurable thresholds. If the service agreement is mushy, the bond is weak, no matter how large the penal sum.

On most facilities maintenance, HVAC service, elevator maintenance, ITS operations, landscape and snow, custodial, or managed IT support deals, the bond does not guarantee “perfection,” it guarantees performance to the standards, frequencies, response times, and uptime levels you wrote into the contract. If your agreement says “provide reasonable efforts to maintain,” the surety will hang its hat on that softness. If the agreement says “achieve 99.5 percent monthly uptime across defined critical assets with no single outage exceeding 30 minutes, excluding force majeure,” then you have something to enforce.

Where these bonds fit and where they do not

I often see two mismatches. First, owners request performance bonds simply because someone in procurement says “we always bond contracts over $X.” That can be expensive and blunt. Second, service providers propose letters of credit or parent guarantees as substitutes when a surety bond would have delivered cleaner recourse.

Performance bonds make particular sense when the cost of interruption is disproportionate to the monthly service fee. Think chilled water plants on a hospital campus, traffic signal maintenance across a county, SCADA system monitoring for a utility, or data center preventive maintenance where a two‑hour outage knocks out revenue. They also make sense where the provider’s failure would leave you scrambling to source scarce parts or specialized certifications.

Where they make less sense: low‑criticality, easy‑to‑replace, short‑term services where the switching cost is trivial. Bonding a three‑month landscaping clean‑up with no complex equipment and five local providers on standby usually adds cost without meaningful risk transfer.

There is also a middle tier where a smaller bond paired with retainage and targeted liquidated damages can outperform a larger bond alone. Complex custodial contracts, for example, hinge on supervision and labor availability more than specialized parts. In that world, the bond supports continuity while the LDs and retainage nudge day‑to‑day quality.

The mechanics, without the legalese

A typical performance bond for a service contract sits between 10 and 100 percent of the annual contract value. Public entities often mandate 100 percent. Private owners might pick 25 to 50 percent when they have fallback options. Premiums range from about 0.5 to 3 percent annually, influenced by the principal’s financial strength, the term, claim history, and the clarity of the contract. Multi‑year agreements are often written as annual bonds renewed each year, or a single multi‑year bond with an aggregate limit equal to the penal sum per year or across the term. The aggregate question matters more than people think. If your five‑year, 20 million dollar service contract is backed by a 5 million dollar bond with an aggregate cap across all years, a heavy claim in year two can leave years three to five with little or no remaining surety capacity.

The surety’s obligations are triggered by a declared default under the contract and the obligee’s compliance with notice and cure provisions. Once properly invoked, the surety typically has several options: finance the existing contractor to cure the default, arrange for a replacement contractor, or pay the obligee up to the penal sum to cover excess costs of completion. On services, “completion” is swiftbonds a misnomer, so in practice the surety either supports a rapid backfill to meet SLAs or negotiates a cash settlement reflecting the documented cost to replace the service at the same level.

One nuance: many service contracts allow for performance failures that are not binary defaults. Think chronic failure to meet response times, parts cannibalization, or missed PMs that shorten asset life. These do not always meet the bar for a default under standard bond forms unless the contract escalates them. Your drafting should ladder SLA breaches into monetary credits, then cure steps, and finally a defined material default. Without that ladder, you will end up arguing with a claims adjuster about whether three months of 96 percent uptime on a 99 percent target is “material.”

Drafting the underlying service agreement so the bond can work

The bond inherits the strengths and flaws of your contract. If you want your performance bonds to carry real weight in maintenance and service agreements, bake precision into the following areas.

- Clear, tiered service levels with objective metrics and reporting requirements. Define response and resolution times per priority class, uptime by asset category, PM frequencies by make and model, cleanliness metrics that are observable, and the data feeds that will evidence performance. A cure structure that escalates. For example, first breach triggers a meeting and corrective action plan. Second breach within a rolling window triggers service credits and an owner’s right to self‑perform or supplement at the contractor’s cost. Third breach or failure to implement the corrective plan triggers a material default. This path makes the timeline and thresholds obvious to a surety. Access and step‑in rights. Give the owner the right to access CMMS data, maintenance records, and vendor relationships upon notice of default. Many disputes stall because logs vanish or vendors refuse to honor pricing after a contractor exit. This clause allows a surety to mobilize a replacement without a long discovery process. Parts, tools, and IP continuity. Require that critical spares inventories, specialized tools, passwords, and licenses be maintained and that title or a right to use transfers upon default. If the service is software support, insist on escrow for essential scripts and a right to continued use for a transition period. This protects against a hollow guarantee where the surety “steps in” but cannot operate. Aggregation of liquidated damages and service credits with the bond. Clarify whether service credits count against the bond’s penal sum and whether liquidated damages are exclusive remedies or sit alongside bond recovery. Both positions exist in the wild. Ambiguity reduces recovery later.

I have seen owners lose six months and thousands of dollars haggling over whether service credits already taken “satisfied” damages under the bond. Write your intent into the contract so the surety can price it and the principal can avoid double counting.

How sureties underwrite service risk

When a contractor bids a bonded maintenance contract, they often assume that their prior construction bonding capacity translates one‑for‑one. It does not. Sureties view service risk differently. They care about financial strength, but they also zoom in on operations: staffing continuity, PM compliance rates, mean time to repair by asset class, software stack reliability, vendor supply chains, and the contract’s incentive structure.

I have sat with underwriters who asked more swift bonds market about a bidder’s fleet age and calibration logs than about their balance sheet. For elevator maintenance, they wanted to know spare part stocking levels by brand and the average number of calls per unit per year. For ITS field maintenance, they checked FCC licensing compliance and the contractor’s network of bucket trucks and night shift capacity. For data center PMs, they probed infrared thermography schedule adherence and breaker testing intervals. That level of detail tells a surety whether the risk is operationally disciplined or seat‑of‑the‑pants.

A strong submission package lowers premiums. It should include audited or reviewed financials, a schedule of ongoing service contracts and performance metrics, safety and quality stats, staffing plans showing redundancy on critical skills, supplier letters for priority access to parts, and a copy of the proposed contract highlighting SLAs and dispute steps. Contractors who present this bundle, rather than just financial statements and a bid bond request, tend to secure better terms and faster turnaround.

Cost, pricing pressure, and who really pays

Premiums for performance bonds on services are typically passed through to the owner via the contract price. Owners sometimes balk, seeing it as a tax for a low‑probability event. Two framing points help that conversation. First, a performance bond is the cheapest form of third‑party risk capital you can buy that both screens the contractor and provides recourse. Letters of credit tie up the contractor’s borrowing capacity and often cost more when you consider bank fees and indirect financing constraints. Parent guarantees are only as good as the parent and can be hard to enforce across jurisdictions. Second, the presence of a bond tends to professionalize both sides. Contractors with surety relationships know that sloppy performance could affect their capacity on future work. That reputational leverage matters.

One caveat: pushing for a 100 percent bond on a maintenance contract without giving the contractor reasonable cure pathways and a fair scope can drive up prices significantly. Premiums rise with perceived claim probability, not just penal sum. Owners can manage total cost by combining a moderate bond percentage with targeted LDs and a thoughtful incentive scheme. For example, a 25 percent bond plus LDs calibrated to SLA failures, paired with an earn‑back for stretch performance, often delivers stronger daily outcomes at lower total cost than a blunt 100 percent bond.

Claims in the service world: how they play out

Construction defaults are usually visible and linear. Service defaults are frequently gray and cumulative. When I get the phone call that a service contractor is “not performing,” the documentation is rarely clean enough to go straight to default and bond claim. The most efficient path usually looks like this in practice: the owner curates a 90‑day performance timeline with dates, metrics, and notices; the contract management team verifies that all required cure notices were sent per the agreement; the owner’s counsel drafts a default notice that cross‑references the failures and the contract citations; and then the surety is notified with a request for a conference. If you jump straight to termination and demand the penal sum, expect a fight unless the violations are egregious.

Sureties have three instincts. First, try to finance and stabilize the incumbent. Second, if the owner’s trust is gone, arrange a takeover agreement with a replacement contractor. Third, negotiate a payment that makes the owner whole for the premium cost of replacement over the contract price. In services, that “premium cost” often includes mobilization, emergency staffing, higher rates for off‑cycle procurement, and the unglamorous cost of reconstructing maintenance records.

Anecdotally, the smoothest claims I have seen hinged on record integrity. In one municipal traffic signal maintenance contract, the contractor let detection tuning and battery replacements slide. Intersection complaints piled up. The owner’s ITS manager had clean logs and photos linked to trouble tickets, plus missed PM checklists. The cure notices were by the book. When termination came, the surety took one meeting to validate the evidence, then funded a takeover contractor within two weeks and paid the cost delta for six months while a new RFP ran. The opposite scenario played out at a hospital where the incumbent did not record PMs in the CMMS consistently, and the owner’s facilities team could not tie failures to missed tasks. The surety dug in, arguing force majeure and staffing shortages. Settlement arrived nine months later at a discount that barely covered the interim premium.

Special considerations by sector

Not all service agreements are created equal. A few sector‑specific points help set expectations.

Healthcare facility maintenance demands infection control protocols and life safety documentation. If the service provider stumbles, replacement contractors must mobilize under those standards quickly. Bonds that include a requirement to maintain a list of pre‑approved subcontractors with hospital clearances shorten the gap between default and continuity.

Elevator and escalator maintenance carries OEM and non‑OEM tensions. Some owners want to avoid lock‑in, choosing independent firms with broad capability. Your bond should address proprietary tool access and software keys. I have seen sureties pay for OEM diagnostic subscriptions post‑default because the contract anticipated it and the parts existed only under that umbrella.

IT managed services and software support involve intellectual property. A performance bond for these services should link to escrow, data portability, and a right‑to‑use license during transition. Without those, the surety can write a check but cannot deliver continuity. This is the rare niche where some owners combine a performance bond with a small letter of credit dedicated to data migration costs.

Utilities and SCADA maintenance face cyber and regulatory overlays. Contract clauses on background checks, NERC CIP or equivalent compliance, and incident reporting become part of the bonded performance. When a default occurs, the surety’s replacement must clear these bars before they log in. Plan for the time it takes.

Snow and ice removal is weather‑volatile. Liquidated damages for late plowing are common, but default thresholds should account for storm intensity. If you want the bond to bite, define trigger thresholds based on snowfall rates and meteorological alerts, not just clock times. Sureties will ask.

Common drafting mistakes that drain bond value

The same errors show up across industries.

Vague definitions of “critical” assets or services undermine enforcement. When the contract says the contractor must maintain “critical systems,” define that list and update protocol. The surety should know what you mean before a crisis, not after.

Unlimited service credits that crowd out other remedies can backfire. If monthly service credits can exceed the monthly fee, contractors start negotiating credits instead of fixing problems. Also, some bond forms reduce the penal sum by the credits, which means you slowly burn your recovery without closing the performance gap.

Ambiguous termination for convenience (T4C) language complicates claims. If the owner uses T4C to switch providers for convenience but alleges performance issues in the same letter, the surety will argue no default occurred. Keep T4C separate from default termination, and follow the cure path religiously.

No requirement for data and documentation handover on default leaves you paying twice. Make the transition package part of bonded performance: CMMS exports, asset lists, warranty statuses, passwords, and physical keys.

Failure to specify aggregate limits across multi‑year terms surprises everyone later. If you expect the penal sum to refresh each year, say so, and negotiate a per‑year aggregate. If not, plan conservatively.

How to right‑size the penal sum

There is no single formula, but I use a simple framework anchored to downtime cost and replacement friction. Map the monthly contract price against the real cost of a failure event, not in penalties but in business impact. For a data center with 250,000 dollars of hourly downtime risk, a 2 million dollar annual maintenance contract might warrant a 50 percent bond because the replacement ramp could take weeks. For campus custodial with predictable labor, a 12 million dollar, three‑year deal might function with a 25 percent annual bond and project‑specific LDs.

Consider also your supply market depth. If three qualified providers can mobilize within two weeks, you need less surety buffer than if only one regional specialist exists. Lastly, look at interdependencies. If your HVAC maintenance provider also manages controls, and controls integrate with your security system, the cost of a stumble multiplies. Penal sums should reflect that compounding.

Relationship dynamics and “soft power”

The presence of performance bonds in service relationships does not have to turn a partnership adversarial. In fact, the best‑run programs treat the surety as a quiet backstop and a second set of eyes. I have invited surety underwriters to quarterly performance reviews when a contractor’s staffing dipped. Their involvement raised the contractor’s attention without escalating to legal postures. The message was simple: your surety capacity depends on performance trends, not just balance sheets. That soft power avoids claims more often than it causes them.

Owners can also use bond renewal as a checkpoint. If the surety begins to hesitate at renewal, that is an early warning signal worth investigating. Conversely, a contractor that improves metrics can often negotiate a lower bond percentage at renewal, lowering total cost while still protecting the owner.

Alternatives and complements: when a bond isn’t enough

Performance bonds sit alongside other tools. Service level credits nudge daily behavior. Retainage gives owners cash leverage. Parent guarantees support small subsidiaries with strong backers, useful when the work is specialized and the group balance sheet is healthy. Letters of credit cover pure payment risk or narrow technical obligations.

When continuity is paramount, owners sometimes layer instruments. I have seen a 30 percent performance bond paired with a 5 percent letter of credit earmarked for rapid transition costs, plus escrow of critical software artifacts. The performance bond covered the medium‑term replacement cost; the LOC covered the first 30 days of chaos. The extra complexity paid for itself when a contractor imploded mid‑winter and the owner had snowplows rolling the next morning while the surety organized longer coverage.

Practical steps to implement without overcomplicating

If you are building or renewing a maintenance or service program and want to incorporate performance bonds without creating gridlock, keep it practical.

- Segment your portfolio by criticality and market depth. Require bonds on the top tier where downtime hurts and replacement is slow. Use lighter tools on the rest. Standardize a clean, metrics‑rich service contract template. Include defined SLAs, cure ladders, step‑in rights, documentation handover, and aggregate bond language. Keep it readable; over‑lawyering makes compliance harder. Start conversations with sureties early. Ask for feedback on your template and whether your penal sums, LDs, and credit structures are insurable without ugly exclusions. Coach your contractors on submission quality. Encourage them to bring performance data, staffing plans, and supplier letters. Better data lowers premiums. Invest in recordkeeping. CMMS discipline, ticket logs, and photo documentation are your best friends if you need to call on the bond.

Edge cases that test the framework

There are scenarios that do not fit the standard mold. Consider performance bonds on energy savings performance contracts tied to maintenance. Here, the performance trigger might be missed savings targets rather than uptime. If the M&V protocol is disputed, the bond claim becomes a battle of math. Avoid ambiguity by hard‑wiring the M&V standard and dispute resolution steps, and clarifying whether missed savings convert into a cash obligation enforceable under the bond.

Another edge case is force majeure morphing into chronic underperformance, for example, a prolonged supply chain disruption or a labor strike. Many service agreements suspended SLAs during the acute phase of global disruptions, but never clarified when normal obligations resumed. If you want your performance bonds to remain meaningful, set time‑bound carve‑outs and require mitigation plans that become part of bonded performance after a defined period.

Finally, joint ventures and prime‑sub models can blur responsibility. If a prime holds the bond but a specialist subcontractor delivers the core technical service, require a bonded subcontract or a back‑to‑back guarantee and audit right. Otherwise, you might end up with a surety financing a prime that cannot actually replace the failed sub, causing long delays before a functional team assembles.

What experienced parties look for before signing

After the war stories and theory, what do the seasoned owners, contractors, and underwriters check before they commit? Three snapshots from real pre‑award meetings:

An owner of a regional transit agency asked the bidder to walk through their Tuesday night shift in detail: who is on call, how dispatch decides between field techs, what spares ride in each truck, how they escalate a failed cabinet lock at 1 a.m., and what three tasks most often get skipped under pressure. That conversation revealed whether the bid price assumed discipline or hope. The surety listened closely and adjusted their appetite based on the specificity.

A national facility management contractor brought a one‑page “bond profile” for the job: requested bond percentage and aggregate terms, performance metrics they could comfortably guarantee, a list of risk‑sharing assumptions (for example, utility outages outside their control), and a proposed cure ladder. That document sped up both contract negotiation and underwriting.

A surety underwriter pushed for a small carve‑out: the bond would exclude purely consequential damages unrelated to replacement services cost. The owner agreed, but in return insisted on a clear definition of what counts as “replacement services cost,” including emergency mobilization, premium labor for the first 45 days, and data migration effort. This clarity eliminated a classic fight after default.

Final thoughts from the trenches

Performance bonds for maintenance and service agreements do not transform weak contracts into strong ones. They amplify whatever is already in place. When the service agreement speaks in specifics, the bond provides genuine protection. When the deal relies on goodwill and vague promises, the bond becomes a thin comfort.

If you are an owner, spend your energy getting the metrics, cure paths, and transition rights right. Price the bond in context, not as a reflex. If you are a contractor, treat the bond as part of your operations story. Show your discipline, not just your numbers, and bring your surety into the conversation early. And for sureties, push the parties toward measurability. Your best claims are the ones you never need to adjust because the threat of enforcement and the clarity of expectations kept everyone on track.

Used well, performance bonds in service contracts create a quiet backbone for continuity. They are not loud. They do not win awards. But on the worst day, when an HVAC chiller trips out in July or a core switch dies at midnight, that backbone is the difference between a controlled handoff and a scramble. That is what they are for.